On the importance of beehive location

If you decide to start a beehive (which you should — it’s a low maintenance pet that makes treasures of delicious food for you), you will find yourself several months later with a honey that is unique to your specific location. My hive makes honey different from that of my friend’s hives located 2 miles away, and honey that is different from the old location of my hives, a few miles further down the road. It all has to do with the local nectar sources in the vicinity of the hive.

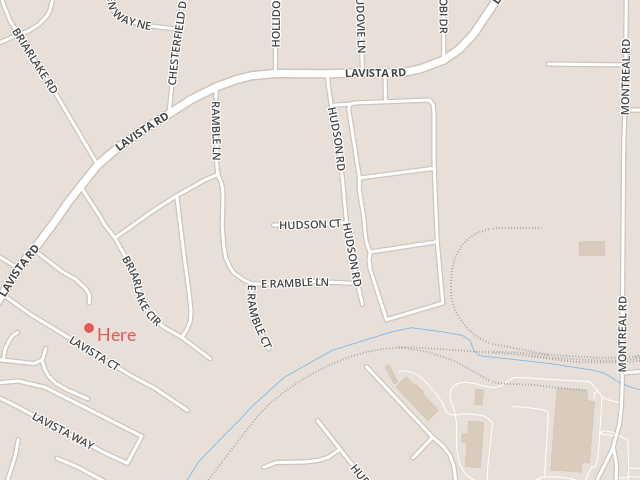

My most memorable batch of honey came from the following location in the Atlanta suburbs:

The hive that made the honey was a swarm that we captured. The resident bee removal gal (who has the wonderful aptronym of Cindy Bee) has too much bee removal work to do, so you can get put on her “swarm list” and become a bee swarm catching cadet: someone finds bees, calls Cindy, and she calls you. You go out to the location and collect your new free beehive ($80 value!). Highly recommended.

We installed the swarm in a top-bar hive in a friend’s backyard and sent them off on their way. They were very productive and very docile, and we could regularly work them without much protection.

Our free hive was a dream — super productive, super nice, few pest problems, and nice orderly comb. We delighted in watching them grow and flourish all summer. We became especially excited when we checked on them in late August and noticed something surprising in their honeycomb.

Our bees were producing white honey. Not only that, they were producing delicious white honey. Like maple, but with some familar unidentifiable taste in there as well.

This was a very exciting development. Supposedly the only plant in the world that causes bees to produce opaque white honey is the kiawe tree in Hawaii, so clearly we had something special on our hands.

Over peanut-butter and honey sandwiches, we began to make plans to ship the honey off to UGA’s apiculture school and get it tested to determine where it came from. Honey can be analyzed under electron microscope to inspect the shape of pollen grains found therein. This is big business, as it can determine if your fancy tupelo honey really is.

Our friend’s little brother came in and sampled the honey.

“This is really sweet. It almost tastes like frosting.”

Hmm.

He was right. It did taste like frosting. But why?

It dawned on us that there were environmental factors we hadn’t considered in placing the hive in our friend’s backyard. This is perhaps best illustrated by an updated map of the hive’s location:

Dumpster diving bees! Children after my own heart.

Unlike the dismay experienced by those in Red Hook, this made our hive even cooler.

Ultimately, I gave the hive to another friend as a present (putting the hive in the backseat of a Corolla, driving at night with all the windows down in full bee protective gear), and frosting honey was finished for good.

Yum.