Concrete Jungle's Fruit Tree Sensors

One of the biggest challenges we face in running and growing Concrete Jungle is planning around the varying schedules of the thousands of fruit trees in the Atlanta area. Some trees will produce early, some produce late, some not at all. Some produce on-schedule but drop their fruit earlier than expected, some produce a bumper crop and should be prioritized, etc.

This is a problem that varies with the type of fruit. Serviceberries in Atlanta were planted almost entirely by Trees Atlanta and the few varieties they’ve planted are quite predictable: we are pretty much guaranteed to be picking serviceberries on May 23rd no matter what. Apples and pears, which are more diverse in variety and make up the bulk of our picking weight, are much less consistent.

Because it’s difficult to know what a tree is doing in a given year, we often simply have to physically inspect a tree. This means we spend a tremendous amount of time wandering around Atlanta, checking on our vast, sparse, urban orchard week-after-week.

Design for foraging

For the past two years or so, Concrete Jungle has partnered with Carl DiSalvo’s lab at Georgia Tech’s school of Digital Media to get a handle on this. Primarily we’ve been trying to develop ways to remotely sense fruit growing on trees. Before we get in to those ways, let’s discuss the partnership some. Why would we want to work with Carl, and why would Carl want to work with us?

Carl’s group focuses on design research, which is exactly what it sounds like: studying how things might be designed. It’s several steps up the chain from actual manufacturing of any physical article. At the design research phase, we have an end goal in mind that we wish to realize but there are several different avenues that could get us to a solution. This is great for us: we know what problem we have and aren’t too picky about how we get there. For a long time we thought of Carl as our crazy ideas outlet and, to a design researcher, a crazy idea starts the conversation. Maybe there is a feasible alternative to the crazy idea. Or maybe the technology to make the crazy idea a reality is just around the corner. Or maybe the crazy idea is really simple if you approach the problem from this direction…

Carl’s group likes us because they already have a heavy focus on food systems, infrastructure and maps, so a local non-profit that maps fruit trees for foraging and donation is a perfect fit.

Now that we’re working together, how do we actually sense fruit growing in a tree?

Drones

Our first approach was to use drones. The apple-pie-in-the-sky idea was to have a drone fly to a fruit tree, take a photo of the tree and return. Also don’t hit any trees, animals, cars or power lines. And don’t freak anyone out, so maybe fly only at night. We’re in fantasyland at this point so the drone may as well also pick some fruit and bring it back for us to sample.

Our drone camera detecting the outline of an apple in the foreground

Our drone camera detecting the outline of an apple in the foreground

We did some preliminary work and started to develop computer-vision software that could identify fruit growing on fruit trees. But this was the apple-pie-in-the-sky idea because it was basically impossible, both because 2014 consumer drone technology wasn’t capable, but because it was legally impossible as well. The FAA had a variety of strange and onerous drone rules in place at the time, requiring flight manifestos, trained drone operators and trained drone spotters for each flight. Carl received an email from the Georgia Tech Associate Dean of Research informing him that “policy of the FAA is that if a FAA-sanctioned institution is caught breaking FAA rules, then the entire institution can have their regulation revoked.”

So that shelved the drone project for a while…what other sensing options did we have?

Ethylene gas sensing

Fruits that are climacteric are fruits that ripen in the presence of ethylene gas. These are fruits like apples, bananas, tomatoes, and melons, and this is the reason people suggest putting some fruits in a paper bag with a banana to encourage the fruit to ripen.

Ethylene sensing would be ideal since we’re directly measuring a gas produced in response to fruit ripening. Ethylene concentration passes some threshold, sensor tweets at us and we go pick it. Easy as.

The problem is that the only ethylene sensors on the market are large units for commercial fruit storage warehouses that are parts-per-billion accurate and likely thousands of dollars per sensor setup (you know you’re in trouble when you see “request a quote” instead of a price.)

There is a company spun out of MIT named C2Sense that has some promising new carbon nanotube-based sensor technology that promises ethylene sensors for pennies apiece. The basic principle of the sensor is that you attach an ethylene-sensitive molecule on to a carbon nanotube, hook up two electrodes to the nanotube(s), and when ethylene is present you can measure some electrical change. Unfortunately, like most companies using carbon nanotubes, they are shipping neither product nor prototype.

(side note about those C2Sense sensors: they used a really cool process to make early versions in the lab. First the carbon nanotubes are functionalized, whereby some the ethylene-sensitive molecule is attached to the nanotube. That’s pretty normal. Making the electrode connection is a bit more difficult, and they developed a neat solution: they took their functionalized nanotubes, compressed them in to a small rod, and put that rod in a standard mechanical pencil. Making the connection between electrodes is then as simple as drawing a line with the pencil.)

Electronic nose

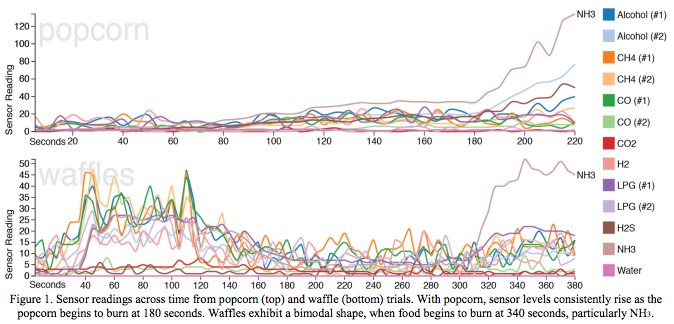

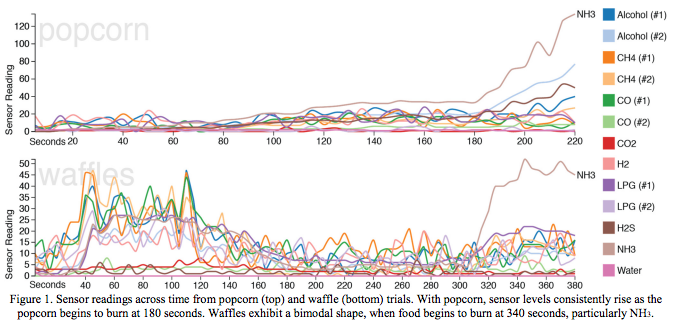

(from “Detecting cooking state with gas sensors during dry cooking”, Ubicomp 2013)

There’s lots of cheap gas sensors out there based on tin oxide semiconductors. Although they are often sold as an alcohol sensor, methane sensor or hydrogen sensor, these sensors can be responsive to a variety of gases beyond what their label indicates, and there are a variety of powerful data analysis methods out there to tease out additional information.

Mechanical sensors

One way that you can tell a pear tree is ready to be picked is simply by how it looks. Its long, thin branches, normally upright, are bent over, laden with heavy fruit. So perhaps we can sense branch bend angle and use that as a proxy for fruit ripeness.

This approach is the most tenuous for producing good data (since branches will constantly be bending and swaying with weather and disturbances), but that can probably accounted for and having a cheap starter sensor will let us develop the rest of the sensor platform so that when an appropriate sensor is available we can drop it in and go.

Human sensors

If we can get passersby to send us photos of a fruit tree, then perhaps that will work out just as well as us visiting the tree in person.

These tie in nicely with Concrete Jungle’s Tree Parent program, where we encourage residents to adopt a local fruit tree and check up on it occasionally, letting us know when it’s nearing readiness. Plus we get some good marketing and educational value out of them.

I covered these in more detail here.

Embedded tree camera

As unglamorous and straightforward as this is, a camera would show us exactly what we want, and we simply have to solve for the infrastructure around it, mostly being communication and power. On a large enough scale, we might have to develop image processing capabilities.

Any other wacky idea

I’ll just leave this here:

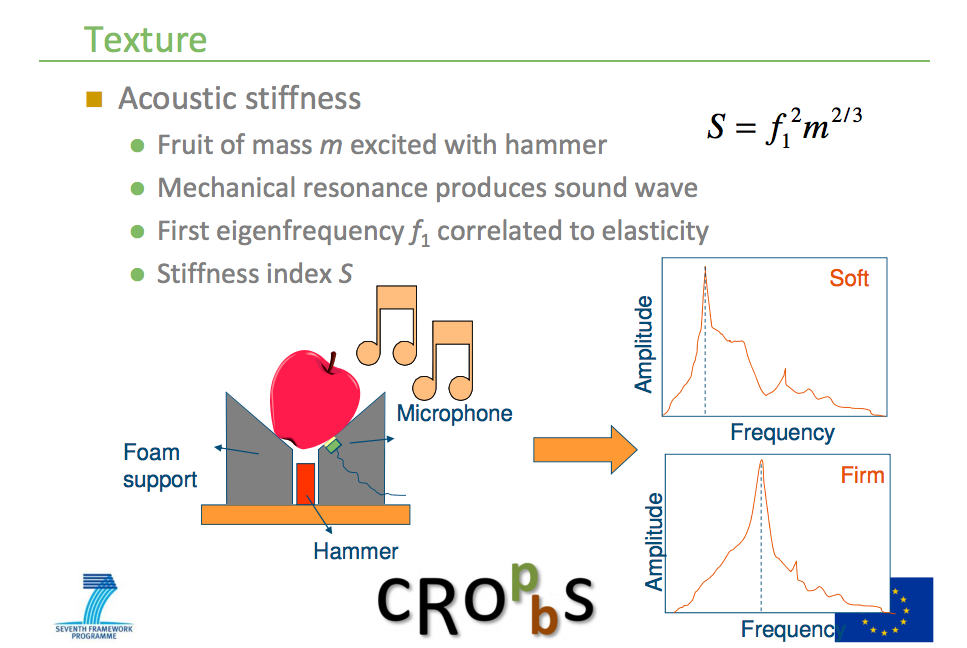

(from the www.crops-robots.eu 2013 workshop)

So how are we progressing? Check out Part 2…